The West Point graduate, who also earned his MBA from Stanford, is 72, but remains barrel-chested and light on his feet. He and his wife live on Ridgefield's Main Street, in a spacious home with a guest house in back.

Bucha has worked overseas for Ross Perot's Electronic Data Systems technology company, served as a foreign policy adviser for then-Sen.Barack Obama during the 2008 presidential campaign and is Connecticut's lone living Medal of Honor recipient, for his valor in Vietnam.

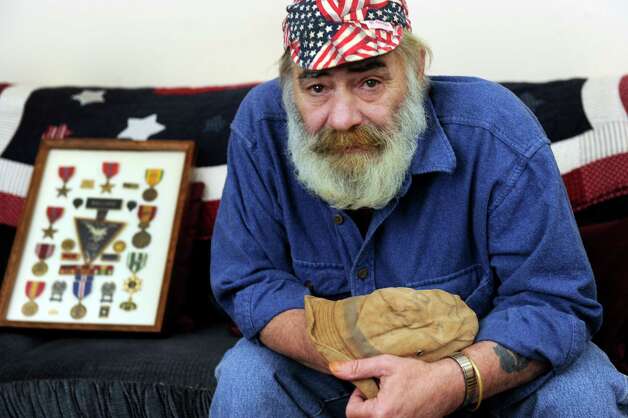

Peter Ballard is 63, and his life, by his own admission, "is not quite a bowl of cherries."

He lives with his wife in a two-bedroom home off Route 37 in New Fairfield -- where he spends most of his time after years in construction left him with severe back problems that forced him to quit working.

Ballard is also a Vietnam veteran, but his service was shadowed by exposure to Agent Orange and a case of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Proud to serve

The lives of Bucha and Ballard might have taken divergent paths after their service, but today, 50 years after the first combat troops went ashore in Vietnam, both men are proud of doing their duty.

And despite his current predicament, Ballard believes enlisting was good for him

"My life definitely would've taken a different turn, and I don't think it would've been for the better," Ballard said. "Going into the military was one of the greatest things that happened in my life."

Bucha feels much the same. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroism on March 16, 1968, when the reconnaissance mission he commanded clashed with a full battalion of North Vietnamese soldiers.

"I never was anything but proud," Bucha said.

"I was proud of the men I was privileged to lead. That's not my medal, that's their medal."

Though the men's views about their service haven't changed, the public's has. At first, returning vets were treated with suspicion, even hostility.

"The more people learned about the war, particularly the Johnson administration, they became more cynical about the government," said Marcy May, who teaches classes at Western Connecticut State University about Vietnam and grew up in a military family.

"People became most more distrustful, and that came to be a problem for veterans. They became symbols of the government."

Ballard was just 19 when he enlisted and, not having been to college, had a hard time finding work when he got back home.

Being a Vietnam vet didn't help. It took him many tries to get a job as a mechanic.

"Nobody wanted to hire you," he said. "If you had that year gap [on your resume], they knew where you were.

"When I came home, they told me not to wear my uniform traveling through airports and stuff. My superiors told me that."

Bucha, by contrast, as a West Point product with a Stanford MBA, was able to rely on his education to make it in the real world. Doors opened, and Vietnam wasn't held against him.

Vets are `cool'

Public sentiments about veterans have changed over the years, and for the better, both men say.

It might have happened when the Vietnam Veterans Memorial opened in 1982. It might have been at the dawn of the next conflict, in Iraq, in the early 1990s. It might still be happening, with movies like "American Sniper" that portray veterans as sympathetic figures.

"The fact that the veteran is now accepted or `cool' has led to wanna-be veterans," Ballard said.

"There are people out there who dress up as veterans and tell you war stories, and it wasn't true."

But if service in Vietnam no longer carries a stigma, both men say they still live with the burden of what they endured there, and they know their brethren do, too.

Bucha, who said he suffers from post-traumatic stress -- he refuses to call it a disorder -- still tries to speak to veterans at least one day a week in an effort to help them cope with their own problems. He tells them about his efforts to control a short temper, and listens intently to their stories.

"What we're trying to do is not celebrate, but remember," Bucha said.

"We're not going to have a party. We're trying to remember the men and women who fought that war, because when they came home, they were not remembered and they didn't want to be remembered."

`Kind of payback'

Ballard helped create the Vietnam Memorial in New Fairfield and speaks to veterans at the town's senior center every month, though he said he is "semi-retired" from that gig.

To him, the reason he helps is simple -- it's the nightmares he still endures.

"Ask me the last time I was in Vietnam: It was last night," Ballard said. "So [working with veterans] is kind of payback. Sometimes you feel like you owe a debt to society."

Dr. May believes that so many Vietnam vets had mental health issues after the war because of how young they were when they entered it.

"The average age of a soldier in World War II was 26; the average age of Vietnam soldiers was 19," she said. "They had less a sense of mortality and vulnerability, and less experience to draw on when they were in crisis. Plus, in World War II, we knew what we were doing there: We're saving the world. In Vietnam, it was about shooting a bunch of people."

Even Bucha, one of the nation's most heralded veterans, still isn't sure what America's goal was in Vietnam. But that doesn't mean he devalues what he and his men did for each other.

"I don't think I'm proud of accomplishing some macro objective, because I didn't see one, didn't know of one," he said.

"I'm proud that the men did not turn on themselves, but stayed together. To this day, they have relationships. To this day, they think of each other as brothers."

Printable Version

Printable Version Email This

Email This Font

Font